Beijing — On a chilly morning late last month, Liu Weidong, a senior executive at China South Industries Group Corporation—a key supplier of munitions to the People’s Liberation Army—became the latest figure ensnared in an escalating anti-corruption campaign targeting China’s defense sector. The investigations, which have intensified over the past two years, are exposing deep rot within an industry long celebrated as a cornerstone of President Xi Jinping’s military ambitions. For a nation racing to modernize its armed forces, the fallout raises urgent questions about reliability and readiness.

The defense sector, encompassing state-owned giants like China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation and Aviation Industry Corporation of China, has been pivotal to Beijing’s push for advanced weaponry—think stealth fighters like the J-20 and sprawling missile systems. Yet, since the ousting of Defense Minister Li Shangfu in October 2023, at least 26 top managers from these firms have faced probes or been removed, according to public records. Li’s expulsion from the Communist Party, accused of “severely polluting the military equipment sector,” marked a turning point, igniting a crackdown that analysts say reveals systemic graft.

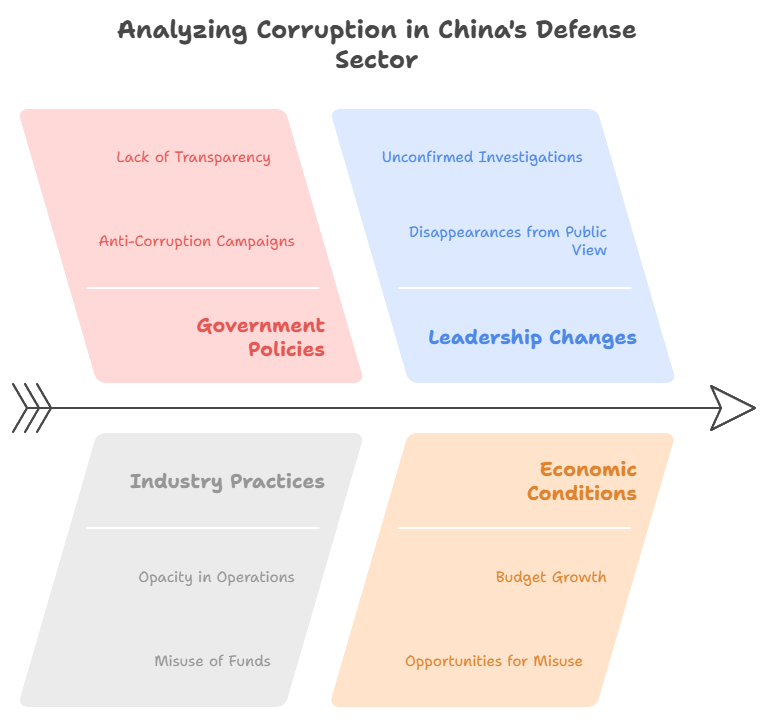

This isn’t a new story. Xi’s anti-corruption drive, now over a decade old, has felled countless officials—last year alone, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection nabbed a record 58 “tigers,” or senior cadres. But the current focus on defense stands out. Companies tied to rockets, warships, and nuclear programs are under scrutiny, their leaders vanishing from public view. Jin Zhuanglong, the industry and information technology minister, disappeared from official listings months ago, though no formal investigation has been confirmed. The opacity is telling.

“The scale of this campaign suggests corruption isn’t an anomaly—it’s baked into the system,” said James Char, an assistant professor at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University who studies China’s military-industrial complex. He points to the PLA’s budget, which has outpaced national economic growth for years, swelling opportunities for misuse. “Equipment spending dominates, and with that comes temptation.”

The stakes are high. China’s defense industry isn’t just about hardware; it’s a political proving ground. A decade ago, Xi tapped its technocrats—rocket scientists and engineers—for their perceived integrity, elevating figures like Zhang Kejian, now a Politburo member overseeing regional economies, from these ranks. Today, that trust is fraying. The Pentagon’s latest China Military Power Report warns that such scandals could erode war readiness, a concern echoed by the Munich Security Conference.

Consider the case of Yang Wei, the J-20’s lead engineer. His profile was quietly scrubbed from his company’s website in January, alongside that of general manager Hao Zhaoping. No explanation followed. Meanwhile, Liu’s firm, ranked 28th globally among arms producers, churns out mortar shells and rockets—essentials for any conflict. If corruption has compromised quality, the implications could ripple across the PLA’s capabilities.

Beijing insists it’s acting decisively. Last July, the Central Military Commission’s equipment department urged citizens to report procurement violations dating back to 2017, when Li led the unit. New regulations, effective this month, demand tighter standards in weapons R&D. Nine state-owned defense firms have vowed to overhaul bidding and hiring practices. Yet, the purge’s breadth—spanning executives, generals, and even universities banned from procurement—hints at a problem too vast for quick fixes.

Critics abroad see more than mismanagement. “This isn’t just about sticky fingers—it’s about a system that thrives on secrecy and unaccountability,” said Bethany Allen, a China analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. She argues that corruption likely predates Li’s tenure, festering in an industry shielded from scrutiny. “It’s hard to believe such rot emerged overnight.”

For China’s leaders, the timing is awkward. Xi’s vision of a “world-class” military by 2049 hinges on this sector. Yet, as Alfred Wu of the National University of Singapore notes, “High expectations clashed with ugly realities.” Li’s fall, he suggests, was a wake-up call—a signal to purge a sector vital to national pride and security.

The cleanup may yield benefits. Song Zhongping, a former PLA instructor, frames it as a necessary purge to “eliminate corruption’s breeding ground” and bolster combat strength. Allen agrees, likening it to “heavy medicine” that could, over time, restore credibility. But in the short term, the damage is palpable—both to Xi’s technocratic elite and to global perceptions of China’s military prowess.

As investigations widen, Zambia’s recent environmental clash with Chinese mining firms offers a parallel: economic reliance on Beijing often masks steep costs. Here, the cost is trust. Can China’s defense industry deliver on its promise, or will corruption leave it hollow? For an international audience watching Beijing’s rise, the answer matters—not just for China, but for the world.